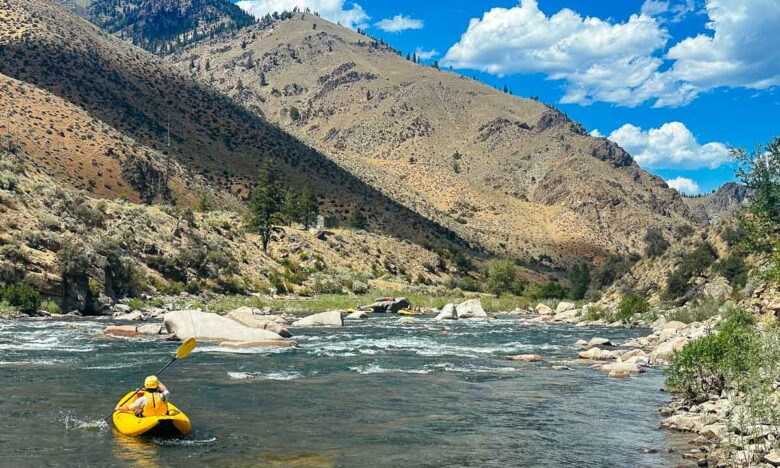

The Middle Fork of the Salmon River flows through a canyon that has held human stories for thousands of years, long before rafts and permits. The first people to live here called themselves the Tukudeka, or Sheepeaters, a small band of the Northern Shoshone who made the Middle Fork their home.

Who Are the Tukudeka?

The name Tukudeka means Mountain Sheep Eaters (tuku for sheep and deka for eaters). They were a peaceful people known for a melodic and sing-song style of speech. Historians believe there were never more than 2000 Tukudeka in the Middle Fork Valley at any one time. Archaeological evidence shows their presence in this area stretches back more than 11,000 years.

Living With the Seasons

The Tukudeka were nomadic masters of the landscape who moved with the changing weather. In summer they traveled high into the mountains to hunt and gather. The Tukudeka never adopted horses due to the steep and rocky Middle Fork canyon. Instead they relied on domesticated dogs to help with hunting and to carry possessions between camps.

When the mountain air turned cold they returned to the river valley to build winter shelters we refer to as pit houses. These were circular depressions topped with wickiups made of wooden poles and rye grass. These structures were surprisingly warm and sturdy. Families often returned to the same winter village for generations to repair and reuse the sites.

Today the shallow depressions marking these homes can still be seen on terraces above the river. We are careful to camp away from them and to leave these areas undisturbed.

Hunting and Gathering

Hunting was central to Sheepeater life, and few people knew bighorn sheep better. They built ingenious traps that took advantage of the sheep’s natural tendency to run uphill, driving them into waiting ambushes. They hunted both solo and in groups, often with the help of dogs, who drove game toward the hunters. They usually finished hunts with knives or spears instead of arrows, saving their valuable obsidian-tipped arrows which were traded from faraway lands.

Fun Fact: Obsidian forms when molten lava cools quickly, creating a glass-like rock that fractures into razor-sharp edges. The obsidian found in Sheepeater artifacts likely came from volcanic areas in southern Idaho, Oregon, and Wyoming. This is evidence of an extensive trade network connecting distant tribes.

They also gathered many plants, including the camas root, a plant still found along the Middle Fork today. Properly prepared, camas was a nutritious food and a powerful medicine used to treat coughs and infections. Salmon was another vital resource.

To prepare for leaner months they stored dried meat, fish, berries, and roots in hidden food caches. Many of which would later play a tragic role in their downfall.

Pictographs: Stories on Stone

Throughout the Middle Fork corridor there are many painted reminders of the Tukudeka. These pictographs are found in places like Rattlesnake Cave and remain the most visible traces of their ancient culture. The paint is a mixture of mostly unknown liquids but the vibrant red coloring comes from red ochre. This is a pigment made from iron-rich clay that is still used in modern paints today.

If you visit a pictograph site please admire them only with your eyes. We don’t touch the paintings since oils from human skin cause the pigment to fade and disappear.

Trading and Craftsmanship

The Tukudeka were skilled craftspeople who used every part of the sheep they hunted. Their hides were especially valuable because of a unique tanning process. They rubbed the animal brains into the skin to make the leather strong and supple. Their trade secret was using two brains per hide. This technique produced leather renowned for its softness and durability and traders sought these hides from across the region.

They also used sheep horns to craft powerful bows. They heated and soaked the horns in the natural hot springs of the valley to reshape them. Once straightened the horns were wrapped in sinew for extra strength. These bows were so powerful they could shoot arrows clean through a buffalo which made them highly prized trade items.

The Sheepeater War

By the late 1800s the peaceful way of life for the Tukudeka was under threat. At the time the U.S. government paid significant sums to those involved in military campaigns and many were motivated by the profit found in conflict. This is corroborated by the journal of Colonel Frank Wheaton who noted that some individuals were anxious for another war to secure more government vouchers.

“[he is] deeply interested in U.S. contracts, and anxious for another Indian War in the Boise Country; he stated that he had then some 25 thousand dollars woth of Government vouchers from last summer’s campaign [the Bannock War] and hoped to secure more this summer.” -Colonel Frank Wheaton in his journal

In 1879 the murder of five Chinese miners became the spark for the Sheepeater War. While the Tukudeka were blamed many historians now point to inconsistencies in the evidence. Some suggest the crime may have been committed by white men to create a justification for removing the tribe from the land though this has never been proven. Regardless of who was responsible the military used the event as a reason to begin the last “Indian War” in the Pacific Northwest.

Despite the name there were never any true battles. The Tukudeka knew the canyon terrain better than anyone and they easily vanished whenever soldiers approached. Frustrated by this the soldiers began a campaign of destruction. They burned winter camps and destroyed hidden food caches to cut off all supplies. When the brutal cold set in and starvation loomed the Tukudeka had no choice but to surrender for the sake of their children and elders. Fifty-one people were eventually relocated to the Fort Hall Reservation in southeastern Idaho.

Where Are They Now?

Though the Tukudeka no longer live in the Middle Fork Valley their legacy is very much alive through the non-profit organization River Newe. In the Shoshone language Newe (pronounced New-uh) means “peoples”. This organization fosters intergenerational learning rooted in Shoshone-Bannock traditional knowledge by running rafting trips on the Middle Fork of the Salmon River for tribal youth.

On these journeys youth are immersed in cultural teachings and traditional practices of hunting and gathering. They share stories with elders and form a powerful reconnection to their ancestral homeland. These experiences help carry forward the story of the Tukudeka as a living and evolving belonging to the land rather than just a chapter of history.

Their Legacy

The story of the Tukudeka is one of incredible endurance and a deep bond with the wilderness. Their spirit still lingers in the canyon walls and the red ochre art in places like Rattlesnake Cave. You can even see their legacy in the bighorn sheep that still scramble across the same cliffs their ancestors once hunted.

When we float the Middle Fork today we are guests in a homeland shaped by thousands of years of stories. The Tukudeka managed to thrive here while leaving only the lightest of footprints. As you enjoy the rapids and the views take a second to appreciate the people who called this wild canyon home long before the rest of us arrived.