Today, due to the threat of nickel strip mining in their respective tributaries, American Rivers has placed the Rogue and Smith Rivers on the 2015 Most Endangered Rivers List. The following is an account of our expedition to document the effect that strip mining would have on the waterways and communities downstream.

Lost and surrounded by vegetation so thick that I could not even fall over, it was hard to imagine the ridge line we were walking is imminently threatened by anything human made. Yet, as it has since the discovery of nickel bearing laterite soil in the Illinois River Valley, the rugged country we were traveling through lingers on the razors edge between preservation and development.

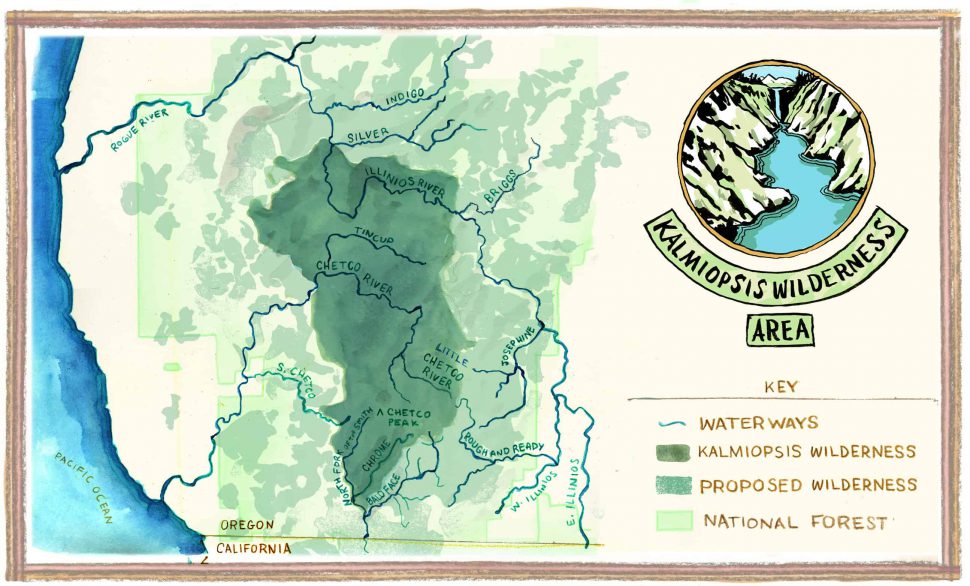

Current plans to develop a nickel strip mine across 1280 acres of Rough and Ready Creek’s pristine headwaters stand to not only irrevocably alter the landscape there, but also pose a looming threat to the Illinois and Rogue Rivers downstream. Ultimately, the combined affront to these treasured public lands, wild salmon and steelhead runs, Wild and Scenic rivers, and clean water that nickel strip mining would create has resulted in the current placement of the Rogue and Smith River watersheds on American Rivers 2015 Most Endangered Rivers List.

In an effort to clearly link the upstream mining proposals to the Illinois and Rogue Rivers, myself and a few of my fellow guides from Northwest Rafting Company, undertook an expedition to document the path of water flowing from the remote headwaters of Rough and Ready Creek all the way to the mouth of the Rogue River at Gold Beach. Even before beginning our hike, as a cougar leapt across the road in front of us, the wildness of the place we would be traveling through was apparent. Two and half more days of hiking with our kayaks in tow only confirmed those initial impressions, as the crumpled landscape left us with little doubt about how Rough and Ready Creek got its name.

Before making our descent down to Rough and Ready Creek, a large portion of our hike followed a ridge that separates it from Baldface Creek and the Smith River watershed to the West. Unfortunately, along with being comparatively beautiful and rugged, Baldface Creek also shares the distinction of being unprotected and host to its own nickel strip mining proposals. Despite downstream portions being protected in California since 1990, nearly half of the Smith River watershed located in Oregon and including Baldface Creek, is still vulnerable to the devastating impacts of mining projects.

The fact that pollutants carried downstream do not stop at state lines has not stopped a foreign owned mining firm from moving forward with plans to develop a nickel strip mine across approximately 4,000 acres of Baldface Creek’s watershed. Facing a similarly devastating threat from a parallel nickel strip mining proposal has led to the Smith River sharing a spot with the Rogue on American Rivers 2015 Most Endangered Rivers List.

Moving past that shared ridge line though, we eventually found an access point for our kayaks on the North Fork of Rough and Ready Creek and began to move downstream. As we made our way to the confluence with the West Fork of the Illinois River, we eventually emerged from the confines of a narrow canyon and on into a broad floodplain that left us scrambling to find enough water to float our boats in its jumble of braided channels. The intact stands of Port Orford cedar and numerous tributary springs we encountered along the way stood in stark contrast to the industrial zone the area would become, complete with ore haul roads and a smelting facility, if the mining claims are allowed to be developed.

Continuing on down the West Fork of the Illinois River brought us past its confluence with the East Fork at Illinois River Forks State Park, and past backyards and farmlands as the river meandered through the communities of Cave Junction and Kerby. Its flirtation with civilization was brief though, and we followed as the Illinois veered abruptly at Eight Dollar Mountain, back into a canyon and toward the Kalmiopsis Wilderness. Leaving roads behind again at Miami Bar, the typical put-in point for groups looking to enjoy the Wild and Scenic section downstream, we spent the next several days traveling through some of Southern Oregon’s most iconic whitewater.

By the time we emerged at the meeting of the Illinois and Rogue Rivers near Agness, it felt like a world apart from where we had begun our journey at Rough and Ready Creek. Following the Rogue downstream, the lush hills of the Coast Range stood in stark contrast to the red tinged, sparse landscape we had started at. Had I not just followed the water myself, I would have had a hard time believing that the Rogue River as it met the Pacific at Gold Beach had anything at all to do with, much less was threatened by, a mining proposal in a tributary of one of its tributaries.

The fact is though, that we had not really traveled as far as our new surroundings would have had us to believe. Our expedition had stretched on for more than week, but had been done at a leisurely pace at low water. Along the way, at least some of the water we had been drinking from, cooking with, and floating on had followed the same path as us and had done it much faster. With a heavy rain, like the sort that can inundate the Rogue River’s watershed during a Pineapple Express storm event, the journey from Rough and Ready Creek to the Pacific could be remarkably quick.

Until our federal agencies act on requests from Senators Ron Wyden (OR) and Jeff Merkley (OR) and Rep. Peter Defazio and Rep. Jared Huffman, to ban or temporarily withdraw the headwaters of the Rogue, Smith, and Illinois Rivers along with Hunter Creek and the Pistol River from mining, the threat to some of our country’s most iconic waterways will remain. Locating a nickel strip mine in any one of these watersheds carries a list of consequences that would travel far beyond the physical scraping away of the landscape.

Thank you to our friends at KS Wild, Geos Institute, The Conservation Alliance, Immersion Research, Base Camp Brewing Company and our generous supporters from Kickstarter for making this project possible.